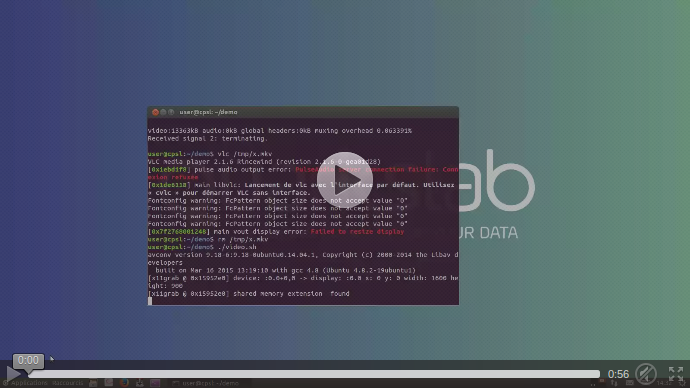

Cappsule is a new kind of hypervisor developed by Quarkslab (to our knowledge, there’s no similar public project). Its goal is to virtualize any software on the fly (e.g. web browser, office suite, media player) into lightweight VMs called cappsules. Attacks are confined inside cappsules and therefore don’t have any impact on the host OS. Applications don’t need to be repackaged, and their usage remain the same for the end user: it’s completely transparent. Moreover, the OS doesn’t need to be reinstalled nor modified.

tl;dr. It’s awesome, I want to test it now!

Give a look at the virtual machine images to test it without any setup. Otherwise, Cappsule requires Ubuntu 16. The documentation gives the instructions to install it through the packages, or build it from the sources.

Overview

Cappsule makes use of security by isolation and runs transparently sensitive software in different VMs. If one of them is compromised, attackers can’t access data outside of it. Here’s a quick and non-exhaustive list of attacks which are ineffective from a cappsule: keylogging, screen recording, file stealing, network traffic interception, hardware attacks from a compromised application (DMA attacks, BIOS or firmware rootkit), etc. Basically, it protects computers against remote software attacks and makes the assumption that the hardware isn’t backdoored. If this assumption doesn’t fulfil your expectation or if you’re concerned about physical attacks, Qubes OS might be a better choice.

Context

Today’s desktop computers situation is catastrophic: users are always at one click away from being pwned and backdoored. Even if the industry developed new security technologies such as sandboxes, they’re far from ideal since kernel vulnerabilities can still be exploited to escape from them.

Everyone is a potential target

This isn’t breaking news; desktop computers are a key target for attackers, being either the final target or the main entry point in corporate networks. One can instantly get compromised in one click, without noticing anything.

Detection isn’t 100% effective

Desktop security is a well-known topic, and a lot of more or less effective solutions were created:

- antivirus: heuristic bypass

- firewall: web and DNS partially allowed

- web proxy: TLS encryption

- hardware probe: untrusted hardware in corporate network

All these solutions share the same idea: to detect, report and/or block potential attacks. Nevertheless, it’s impossible to detect 100% of attacks. That’s why Cappsule doesn’t detect them, but confine them.

Sandboxing isn’t enough

Software security evolved a lot during the last 10 years. Countermeasures in the kernel or userland were continuously improved to increase the difficulty for attackers to develop working exploits.

During 2005, Microsoft introduced the notion of sandbox into their web browser, Internet Explorer. Nowadays, almost every web browser gets a sandbox. Sandboxed processes are executed within very restrictive environment, which limits the consequence of vulnerabilities in plugins or renderers.

Nevertheless, sandboxes have limits. Sandbox bypasses are commonly found because of loose security policies or from vulnerabilities in the sandbox itself. Even if the sandbox implementation were perfect, it relies on the OS features to restrict the environment. A vulnerability in the OS could enable a sandbox escape, and there’s not much one can do to fix that. Even if syscall filtering (thanks to SECCOMP on Linux) is used by a few sandbox (e.g.: nacl), some syscalls still need to be allowed and the attack surface remains significant. For instance, the Linux futex syscall can’t be filtered because the libc relies on it to implement mutexes. A working exploit for the futex vulnerability (CVE-2014-3153) found by comex allowed to bypass every sandboxes.

Despite these limitations, sandboxes are another layer (sometimes effective) of protection that attackers need to bypass in order to compromise the system, and kernel vulnerabilities are a common way to escape them.

Hardware virtualization

Cappsule uses hardware virtualization to launch applications into lightweight VMs, which run a copy of the host kernel and have no access to the hardware. If an attacker manages to break into the VM (through a bug in the application for instance), the attack is confined into the VM. Even if a kernel vulnerability went to be exploited, the attack remains in the VM, and the attacker has no way to access to the host.